By Konye Chelsea Nwabpgor

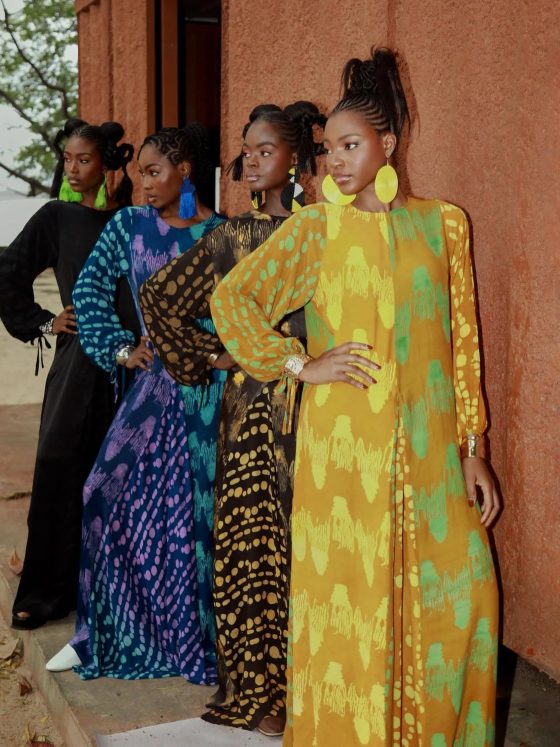

It’s a common sight these days—scrolling through social media only to stumble upon people venting about the soaring prices of Nigerian fashion brands.

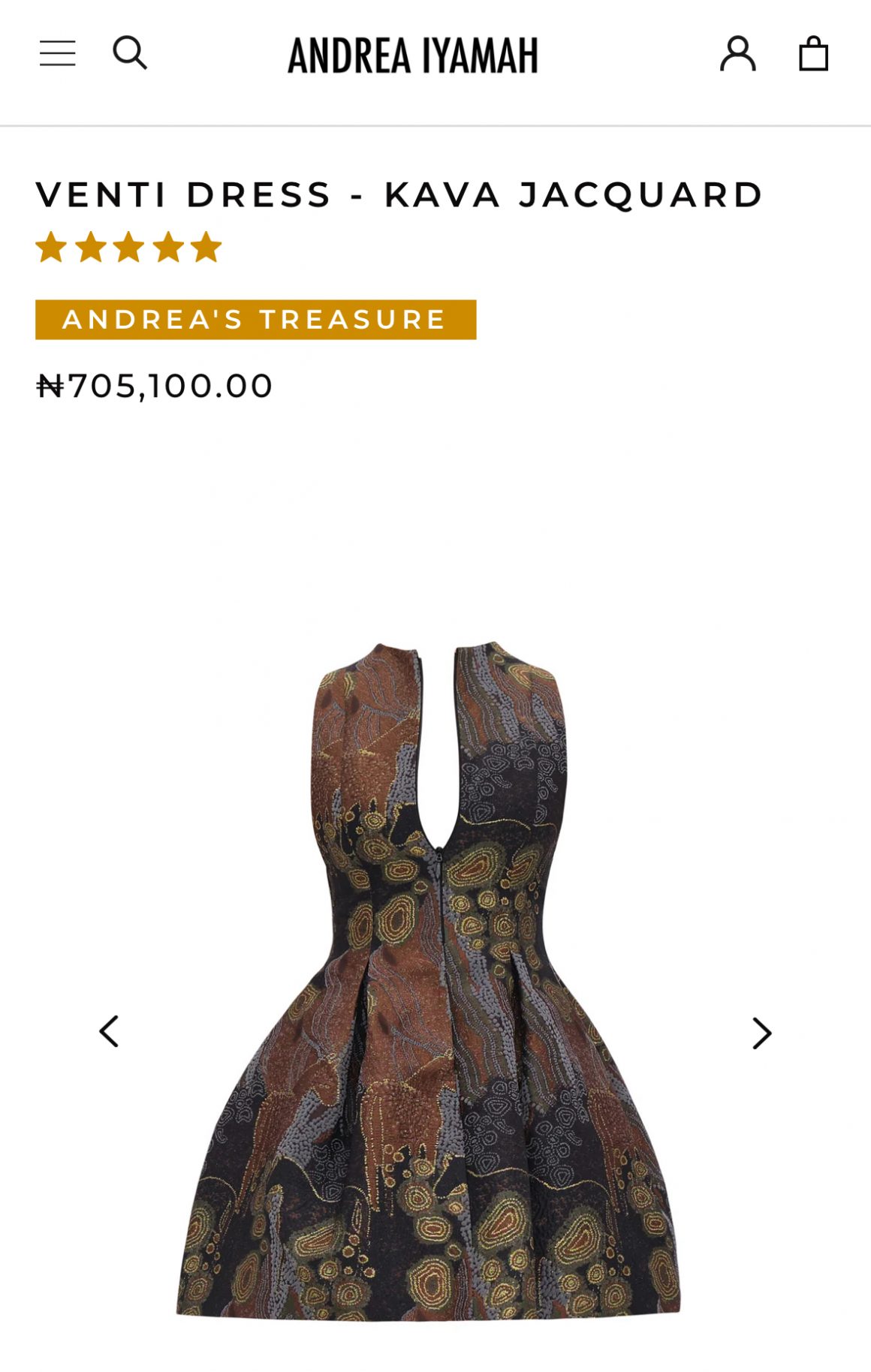

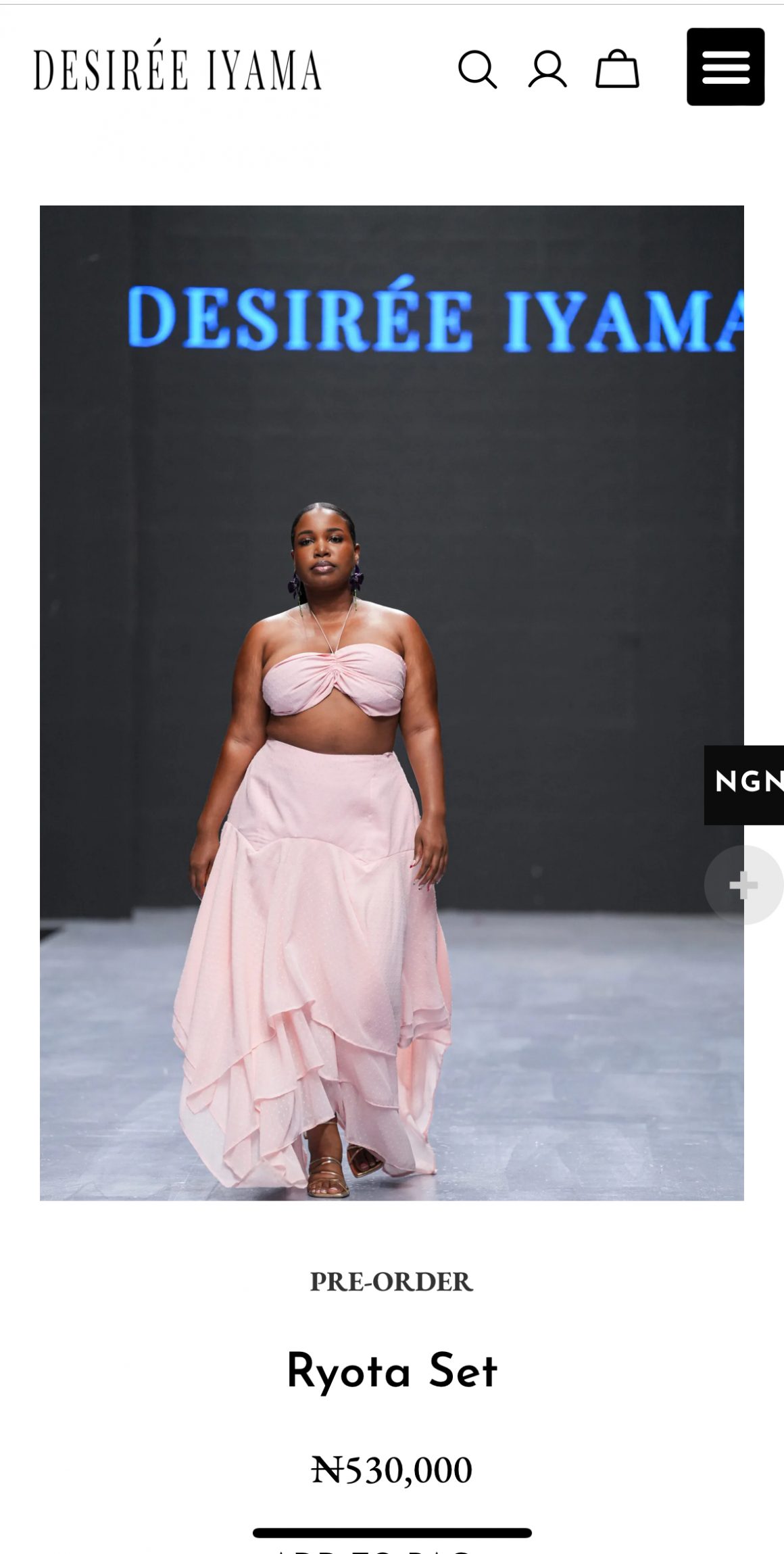

With inflation eating into everyday expenses and incomes largely remaining stagnant, fashion has taken a backseat for many. To put things into perspective, the price of a single piece from DNA by Iconic Invanity can climb as high as 650,000 naira, enough to make anyone second-guess if they really need that statement dress. Banke Kuku’s eye-catching Purple Bubble Embellished Bodysuit is tagged at $1,004.00—at today’s exchange rates, that’s nearly the cost of rent for many in Lagos. Hertunba, another celebrated local brand, offers pieces that go up to 600,000 naira, while Desiree Iyama’s creations can fetch up to 500,000 naira. Fashion, no doubt, comes with a hefty price tag in Nigeria.

The price gap between the average Nigerian’s earnings and the cost of these brands has many wonderings: What makes these pieces so expensive? For many designers, the answer lies in the process. A piece from these brands isn’t churned out by the dozen. Each garment might take days or even weeks to complete, often involving hand embroidery, meticulous detailing, and a level of craftsmanship that rivals global luxury brands.

It’s easy to see where these designers are coming from. Unlike global luxury brands that have factories in China or Bangladesh, many Nigerian brands still manufacture in-house, often relying on local artisans whose skills are becoming a rare commodity. This craftsmanship doesn’t come cheap, and the scarcity of high-quality materials only drives the prices up. As Desiree Iyama once remarked, “When you consider the cost of production, it’s almost impossible to make something high-quality and affordable in today’s Nigeria.”

Yet, there’s a difference between understanding a price and justifying it. And that’s where the debate gets tricky. For a growing number of consumers, even the acknowledgment of quality fails to validate the price tags. They argue that while these brands undeniably deliver exquisite designs, the cost still seems disproportionately high, especially given that the average monthly salary in Nigeria is around 250,000 to 300,000 naira. Therefore, splurging on a 600,000-naira dress becomes a choice few can afford, effectively making Nigerian fashion an exclusive club for the affluent.

Moreover, there’s the issue of value versus brand identity. Folake Coker’s Tiffany Amber, for example, has a strong brand following, with pieces that boast intricate designs and luxurious fabrics. For the well-heeled client, wearing a piece from her is as much about the design as it is about what the brand represents—affluence, status, and taste. But for the average Nigerian, these prices scream “aspirational” in a way that can feel exclusionary.

Social media only fans the flames of this debate. As influencers flaunt Nigerian designer outfits on Instagram, the divide between those who can buy into the lifestyle and those who can’t becomes glaring. The idea of fashion as a language of identity and pride begins to wane when it becomes evident that only a select few can afford to speak it. It raises a bigger question: if Nigerian fashion is too expensive for Nigerians, who is it really for?

Some designers, recognising the growing outcry, have argued that they are simply responding to the demand for luxury and exclusivity. “Nigerians appreciate quality, and they’re willing to pay for it,” said one Lagos-based designer. And this is largely true—Nigerian consumers who have the spending power often choose local luxury over international brands. There’s a unique pride in wearing something that celebrates Nigerian craftsmanship; for some, that pride is worth every penny. However, as the economy tightens, many question how sustainable this loyalty is, especially when even the wealthy are feeling the pinch.

One could argue that this isn’t a problem unique to Nigeria. In fact, many African designers across the continent face the same dilemma. To maintain quality, brands are forced to import expensive fabrics, sometimes even sourcing internationally trained artisans to meet rising standards. South African designer Laduma Ngxokolo, known for his Maxhosa knitwear, faces similar price debates in his own country. But with Nigeria’s added economic challenges, the discourse feels more urgent and polarising.

As Nigerian fashion’s luxury segment evolves, we’re left with a complex paradox. On one hand, these brands represent the pinnacle of African creativity and an aesthetic rooted in culture and identity. On the other, they reflect an economic reality that continues to sideline the average consumer, one who could very well be the industry’s most loyal supporter if given the chance.

So, what does the future hold? Some designers have hinted at diversifying with more accessible lines, while others hold firm, believing that their niche lies in the exclusivity. One thing is clear: Nigerian fashion has become more than just clothes; it’s a statement, a symbol, and sometimes, a struggle.

As consumers, we’re left to decide whether to continue applauding this rise in African luxury or to question how much of it is sustainable and inclusive. In the end, perhaps the true measure of Nigerian fashion’s success isn’t just how much we’re willing to pay but how it resonates with us all, whether we wear it or simply watch from afar.