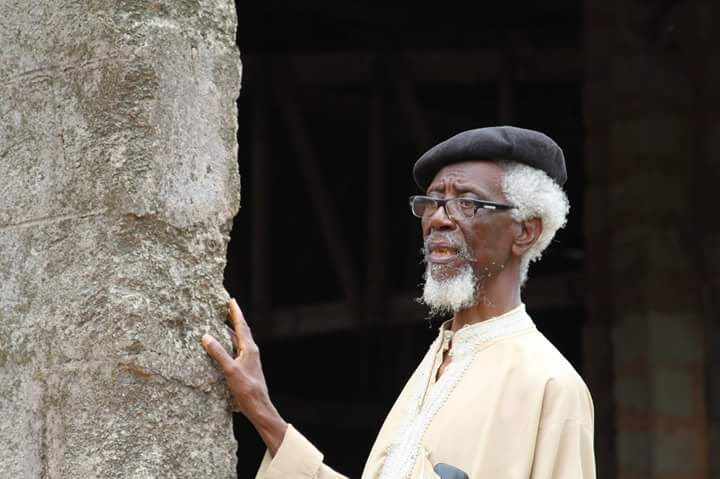

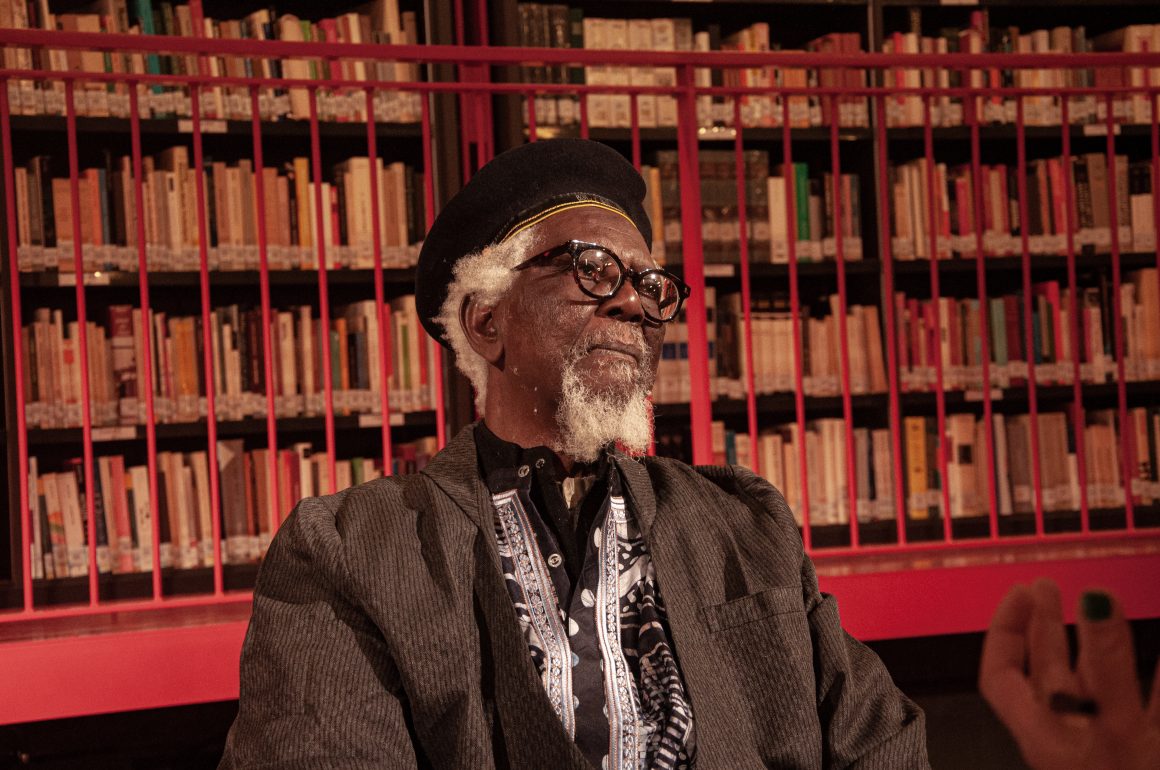

Demas Nwoko is a visionary architect, designer, and sculptor whose artistic prowess knows no bounds. With a trailblazing spirit, he stands at the forefront of Nigeria’s modern art movement, blending indigenous African building techniques with innovation in architecture. His influence on contemporary African theatre through his mesmerising stage designs is nothing short of profound.

In 1960, Demas took the art scene by storm as a founding member of the Mbari Club of Ibadan, a vibrant hub for cultural exchange among aspiring Nigerian and foreign artists. Together, they kindled a creative fire that would forever shape Nigerian art history. And as if that wasn’t enough, he also proudly stood as a member of the Zaria Rebels, a dynamic group of artists championing the concept of “natural synthesis.” These trailblazers fearlessly fused their Western art education with the essence of African themes, birthing a new era of artistry that transcended boundaries.

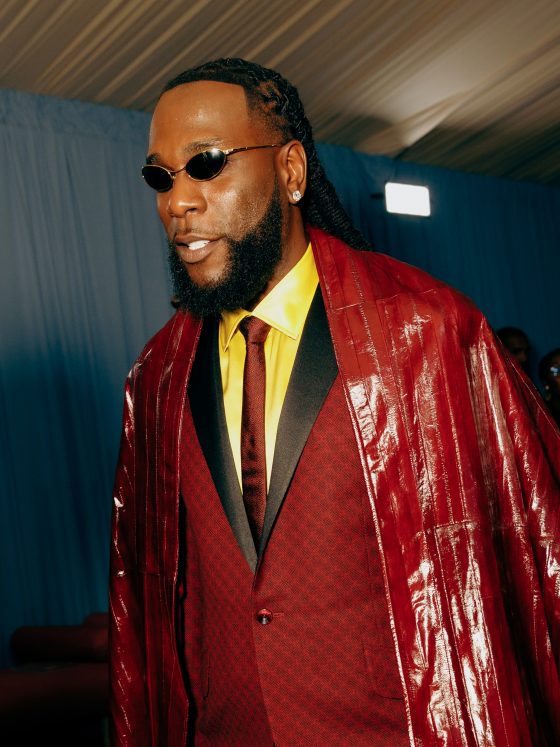

Throughout his illustrious career, Demas Nwoko adorned the world with exceptional murals and awe-inspiring public commissions. His artistic ventures garnered accolades and admiration from all corners, culminating in a crowning achievement at the 2023 Venice Architecture Biennale. There, he was bestowed with the prestigious Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement, an honour that celebrates his remarkable contributions to the world of architecture.

In a captivating conversation, Nwoko unveils the seamless interconnectedness of his careers as an artist, sculptor, and architect, delving into the natural flow of inspiration that binds them together, allowing him to craft masterpieces that resonate with the essence of life itself.

As one of the few surviving members of the Mbari Club, how does it feel to have been part of an unforgettable history that has become a watershed of creative arts education in Nigeria?

The Mbari Club was founded by a group of contemporary creative minds who had recently graduated from different tertiary institutions. We were either writers, classic artists, or playwrights, and our formal training in these areas began during our time in our institutions. After leaving the university- which was a bit organised and controlled- we knew that we had to create for the people and contribute to the community. Since our creations were new, we could not continue to practise as traditional creative people. The primary language of our creations was predominantly English, which was a foreign language. This meant that our new creations were also predominantly foreign. Everybody believed in the new acquisition, and we were all very enthusiastic about propagating our new creativity, which was not in any way a repetition of the tradition but more – in the physical appearance – foreign. To provide a space for us to practice, the Mbari Club was formed, bringing together creative artists and writers. It was the most sensible decision to make at that moment. We all had faith in the path that we had chosen. It wasn’t a matter of choice; rather, those of us who initiated this new movement based on a new culture took it as a duty to disseminate our own creativity.

I wouldn’t say we were special because we relied on coming together and collaborating to encourage and advance our creative pursuits, as they differed from what we knew in tradition.

Again, apart from expressing ourselves, we had another deliberate reason for creating this platform. The content of our creations was already reflecting a clear trend, rejecting outright acculturation, which means abandoning our own traditional culture in favour of the foreign culture imposed by colonialists. Our creations were a form of rebellion against the teachings we had been subjected to in school. We were rejecting these teachings and instead propagating an amended version of our own culture. This required a certain kind of courage to pursue. It was a parallel effect. It was a parallel activity. Not one that required beating of our chests. So, how do I feel? I feel we did the right thing, but “How has it turned out?” is another story. Because, like our people say, “The greatest farmer, it is not what he was seeing when he was going to farm that he’ll be seeing when he’s coming back because what he must have found in the farm would have been completely different from what he thought he would find.” I would say that we can’t beat our chests too much. It’s still a struggle because cultural progress has not been as smooth as expected. Therefore, I wouldn’t say that we should be congratulating ourselves. I don’t think the trend we tried to propagate has caught on today. There seems to have been almost a complete reversal.

You were recently awarded the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement at the 2023 Venice Architecture Biennale. How was that experience for you?

Receiving an award is not much of an experience for me anymore because I have been honoured and toasted many times on several occasions. However, this particular award turned out to be more significant than I initially thought, not just one of those for recognition of your effort.

The event took place in the centre of European creative civilisation, the town where, in hindsight, I found that I was almost roped into first practising my career formally after my training in Paris. In that same town, Venice, which was at the time a famous location for opera performances, I was hired as a designer in the theatre.

During the award show, I came across pavilions representing various countries. It was an annual opportunity for their citizens to display their creative work. I noticed that Nigeria and Africa were noticeably absent from the event, indicating a lack of organisation and development when it comes to nurturing our creativity at home. This shows in our economy, technological development, and the extent of our connection to the contemporary world. Being the first African to be present there to receive such recognition was a very humbling experience.

When one looks at your portfolio of work in visual arts, theatre and architecture, there’s a palpable connection in those areas in which you have invested several years of experience. Would you say it was a seamless transition to swing from one area to another?

I didn’t really transition from one area to another. From childhood, I was inclined to the profession of architecture. I believe this must have been passed down in my genes from my father, who also enjoyed designing houses. In addition, I was also aware of our traditional architecture and in secondary school, I also studied fine art, which ended up being similar to architecture. Both involve design in a way, as well as the expression of aesthetics. I found that I was quite good at drawing and painting.

When it was time to pursue my studies in architecture, I discovered that the formal study of architecture was a bit too technical and too dry. It didn’t have any element of creativity. The emphasis was on draftsmanship. Architecture was virtually an organic type of form that served as a habitat for human beings. Hence, I chose to suspend the formal study of architecture. Instead, I decided to deepen my consciousness of creativity in form and colour and increase my awareness of nature’s creativity in the environment. I thought that I would go on to study architecture after I graduated in fine arts. However, I was introduced to the theatre, designing the stage decoration. Here, I found that I was a bit defective as it required more than the knowledge and practice of visual art. I was and am still always up for a challenge. I am willing to explore areas that I am not familiar with and suspend any preconceived notions. So, when the opportunity arose during my postgraduate studies, I made the decision to study stage design.

At the end of my studies and after completing this stage design, I got the chance to create a design for an opera in France. The success of my work led to them expressing interest in hiring me for a permanent position in their theatre, but I didn’t take the job.

As I mentioned before, my first career practice was in the theatre. But you see, that happening didn’t mean that I had dropped the other areas. While I was working in the theatre, I was also painting and sculpting, and I even started practising architecture when the occasion arose. So it was not that it was one after the other. No, I was practising everything at the same time. Because for me, it was very easy to do that because the process of creating forms and expressing aesthetic creativity is grounded in the same aesthetic philosophy. Essentially, it is a universal language shared across various artistic disciplines.

So I sculpted as I painted; I painted as I designed stage sets. I did stage design as I designed buildings. It was a simultaneous practice of all these disciplines rather than a linear progression.

You have consciously worked with the sustainability mindset when selecting the materials (e.g., clay) you use for your designs. What informed that decision early in your career as an architect? How did you create that distinct style as an artist and an architect?

It was an aspect I found lacking in my formal architectural training. They concentrated on creating exciting designs without regard for the costs of implementing them. I can clearly make this statement: a design that is not built does not exist. The cost of realising a design must be the foremost consideration before putting your design together.

Your client must be able to afford to execute whatever design you have made for him. Designing buildings is a task that should benefit everyone involved, so it’s important to prioritise creating affordable and sustainable designs. After all, affordability often leads to sustainability since more people can afford it.

To be a successful architect, ensuring client satisfaction by creating affordable and sustainable designs is crucial. This entails considering the cost of materials and opting for the most economical options. I created iconic designs for large municipal buildings, such as churches and theatres. I always remained focused on the importance of using materials that were accessible to others as well. I wanted to prove that inexpensive materials did not compromise the excellence of a design and that remarkable designs could still be achieved using the same materials as modest ones. I had to make all my designs this way to uphold this philosophy.

You have made some remarkable scholarly contributions. Recently, you launched a compendium of your articles. How do you find time for research and documentation?

You see, all of my activities are not in compartments. They are all related. While I was teaching at the university, I did not practice research and publication just as an exercise to gain promotion. No, I practised them as part of my professional practice to engage with others on the issues at hand that concerned those areas of my profession or cultural philosophy in general. They were natural activities for me.

I attended various forums, and to participate, I wrote my own essays on the subjects, expressing my personal views. Sometimes, it became repetitive because I focused on forums related to my field of work. Nevertheless, it was painless. The compendium had to be published later in my life to achieve its purpose. It would have been published long ago if I followed the academic practice, but I didn’t want that. When one reads through it, it comes across like a free-flowing speech, much like how I speak in person, rather than like hard research and documentation.

And why are such writings so important to you and Nigerians at large?

They are very important because they establish my philosophy of life and my belief as to what our new culture should be.

I want everybody to read them as they address current issues that still require attention. None have happened or happened as I believe they should have. These writings will remain very fresh and topical until they are applied.

Many Nigerians will argue that the nation has been more divided along tribal lines in recent years. Looking back at your associates in the Ibadan years, would you say that Nigerians were more detribalised then than now? How did you manage to stay as friends in those years or even till now?

Everyone belongs to one tribe or the other. Staying with your own tribe does not make you a tribalist. We are a nation-state, meaning that we are made up of many tribes that were amalgamated.

When our cosmopolitan towns were being built for the first time, people flocked to these centres to participate in the daily activities of these places and pursue their respective professions. It was general knowledge that people spoke different languages and came from different tribes. “Tribe” was not an issue, or so it seemed. Everybody concentrated on what brought them together. At that time, it looked as if there was no tribalism, but as independence approached and the colonialists prepared to hand over governance to us, another part of society manifested. Unfortunately, leadership became competitive at that point. We had to adopt the foreign model of democracy, which needed elections, political parties, and all that. You’ll find that the first political parties emerged with a national focus, but as independence approached, everybody started eyeing the juicy parts of leadership.

The citizens started gravitating back to their centres of origin to acquire the full support of their own people. They believed that the numbers back home could help them acquire leadership. At that moment, people realised that we were not really one and had to organise ourselves to ensure we were not sidetracked or disadvantaged.

As everyone returned to their respective camps or trenches, the next step was negotiating to be together. That brought in the element of leadership being dispensed turn by turn. That’s how, as we developed our modern democracy, instead of coming together, we are finding ourselves back in our camps, waiting for our turn. This has created more dissension and tribalism. In fact, damaging tribalism. Today, we’re not sure of our citizenship. You might be born and raised in a region or a town, and your fellow inhabitants refer to you as a stranger element. You are disenfranchised because you are never allowed to hold any political posts there. That is why it looked as if the beginning was very rosy. Everybody was free. The political power rested in the colonial hands, you see. However, after gaining independence, Africa has witnessed escalating differences due to the competitive nature of European democracy, which is very un-African because African democracy is based on consensus. Everybody had to agree.

In contrast, the European one is survival of the fittest. Living apart had to become more evident today than it was in the beginning. For me, we are still searching for the best new culture to adopt because what we have now is not really ideal. We have to find how to live together as one people, no matter what language you speak, what area you come from, or what religion you are from.

When we look at the trends in arts, design, and fashion, we can see that creatives have a way of reclaiming history by tapping some elements from one period or another. How does having a sound history knowledge help a creative find his or her own voice?

Yes, traditional history is the storehouse of the people’s creative culture.

In fact, there’s a general saying that there’s nothing new under the sun. If you read the history of people thousands of years ago, they look like us today. The familiar helps to create stability in the environment. If you install new things that people have never seen in the environment, you create problems for them in resolving their existence within such an environment. You have to be with the known before you can really interpret the new.

You find that when the train starts running riot, the tendency is for the people to slow down, go back to their past and pick something that everybody can remember. Then, a new stability is created.

You cannot simply create something entirely new. You find that you have to start with what you know. Then, innovate on it. You can’t just create a brand-new thing that doesn’t exist. Yes, it is done, but I think that does not go down well with the people. In fact, it causes a health hazard, a mental health hazard.

We need a stable, familiar environment to have a stable life. It’s the duty of creative people to ensure they create such an environment. So it’s not surprising. Take language, for example. You can’t just change a language. No. You can only bring new elements of other languages into it. The language remains the same forever or until another completely swallows it up. It’s a natural process. It’s a natural thing to happen in the world of fashion, art and design; it’s quite common to see the reintroduction of old elements.

Today, technology is changing the way artists express themselves. Actors are leaving the stage to perform for social media consumers. Artworks are being coined and sold on online platforms. How do you engage with technology for a man your age? Are you apprehensive or simply curious about technology?

It is, in fact, the way you people see technology that is wrong. Technology is as old as man because it is the process through which man brings into physical being his creativity. He creates tools to work. These tools continue to grow or change. It might not be even better, but it continues to change. That it’s changing doesn’t mean that the change is really what should happen to create a sustainable society. But it’s just that the trend comes in, and it facilitates production.

I will give you an example. In the building industry, there was a shift away from the traditional way of building walls – hand-moulding mud into pear-shaped blocks and then joining them with the wet mud on top of each other. The Europeans brought the technology of shaping mud into a form using moulds. They created rectangle-shaped moulds using either wood or metal. You would put earth inside a mould, shake it and remove it, resulting in uniform shapes that could be stacked to build walls.

Technology improved, and the Europeans created machines to create these forms. The new block-making machines were automated to produce multiple blocks simultaneously—10 to 20 at a time, and more. The block industry blossomed. Recently, I’ve taken stock, and I found that they don’t use these new machines in most places anymore. They are now using hand moulds on the floor just like it was done initially. This they find more cost-effective than using the machines. Man will gravitate to the most advantageous type of technology. You don’t have to stick to technology that is not viable or affordable. After some time, everybody gravitates to the most affordable one. Most of what we call advanced technology today are really useless. They are not affordable.

With the deregulation of fuel, people started saying, “Ah, maybe we start riding bicycles”. Yes, it might come to that, but you’ll find that most people will return to foot. Foot transportation.

It may sound funny, but I remember when I was younger, we visited Lagos as students and walked from Ikorodu Road to Bar Beach. That was the only means of transport because of the few buses that existed; how many people could fit in them? In the village, we were attending schools 10 kilometres away, and children walked that 10 kilometres, up and down, every day. This was normal. Today, ask a child to do that, and he will say no, but soon, they might have to start doing that because the cost of transportation is really not affordable.

Technology should better be interpreted as the means of production that is most affordable and most confident for the people. You don’t have to adopt technology for its sake. The application of technology in the production of creative items is precisely as I’ve just described; if you were a printmaker like my colleague, Bruce Onobrakpeya, you had to own a printmaking machine. While the others who were painters continued to use their hands manually, on their papers or on their platforms.

Who is the more modern artist? Nobody. The application of technology is as you need, and that is why the phrase was coined “appropriate technology”. The fact that others are flying around in rockets doesn’t mean that everybody must fly around in rockets. Technology should be owned by each people. They should advance it according to their need and create whatever they want within their resources.

Everybody has practised technology since time, and the technology tomorrow is not necessarily the best thing to happen to man. On the other hand, let us look at what unbridled advancement in the use of materials has led the world to today. Global warming, the over-exploitation of natural resources, conflict, all that just because you want to create a new thing, a new technology. Even now, the innovations we call advanced technology, rocket science and so on are optional.

They are just a means of making money because most of them are unaffordable. We should be very weary when applying technology, ensuring it is within our capability and meets our needs. If you find that it’s cheaper for you to make some physical items manually and use them the way you want, you should continue doing that rather than forcing yourself to live a false way of life. That is very, very dangerous to existence. Technology should always be within the need, ability, and affordability of every people.

How do you relax or have a good time now that you are not under pressure to work?

I don’t know about that. I’m working today as much as I was working 50 years ago. My staff can bear witness to the fact that they can barely keep up with me at work. I don’t think I will change until my creator calls me.

When it comes to relaxing, I relax at my work. It’s not all the time that I’m in the office or the studio doing physical work. Sometimes, I sit down and doze off, you know, and have a good sleep, then I get up at closing time, close my office, go to my bedroom and continue resting. I find my rest in my work.