History being made is often a topic of retrospective conversations, and once in a while, we are lucky to witness it first-hand by living in and of the time when it happens.

In the movie industry, the Academy of Moon Picture Arts and Sciences has created an elite class of ‘chosen ones’ over the years in the shape of their Oscar nominees. They are the best of the best in a competition more fierce than most. These nominees have become some of the most talked-about individuals in the world, from Tatum O’Neal being the youngest Oscar winner in history at the age of 10 for her performance in ‘Paper Moon’ in 1974 to Lily Gladstone being the first ever Native American to be nominated for an Oscar for her performance in Marn Scorsese’s historical drama, The Killers of the Flower Moon, in 2024. They are quite simply a cut above the rest.

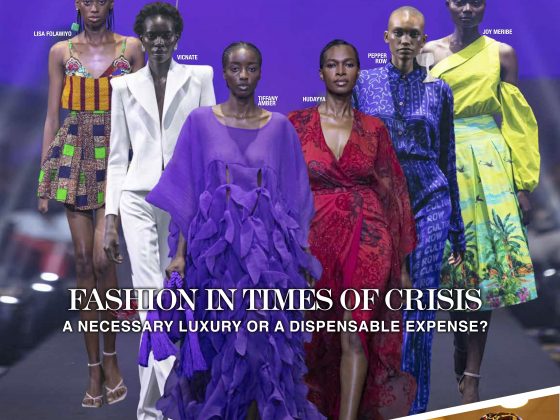

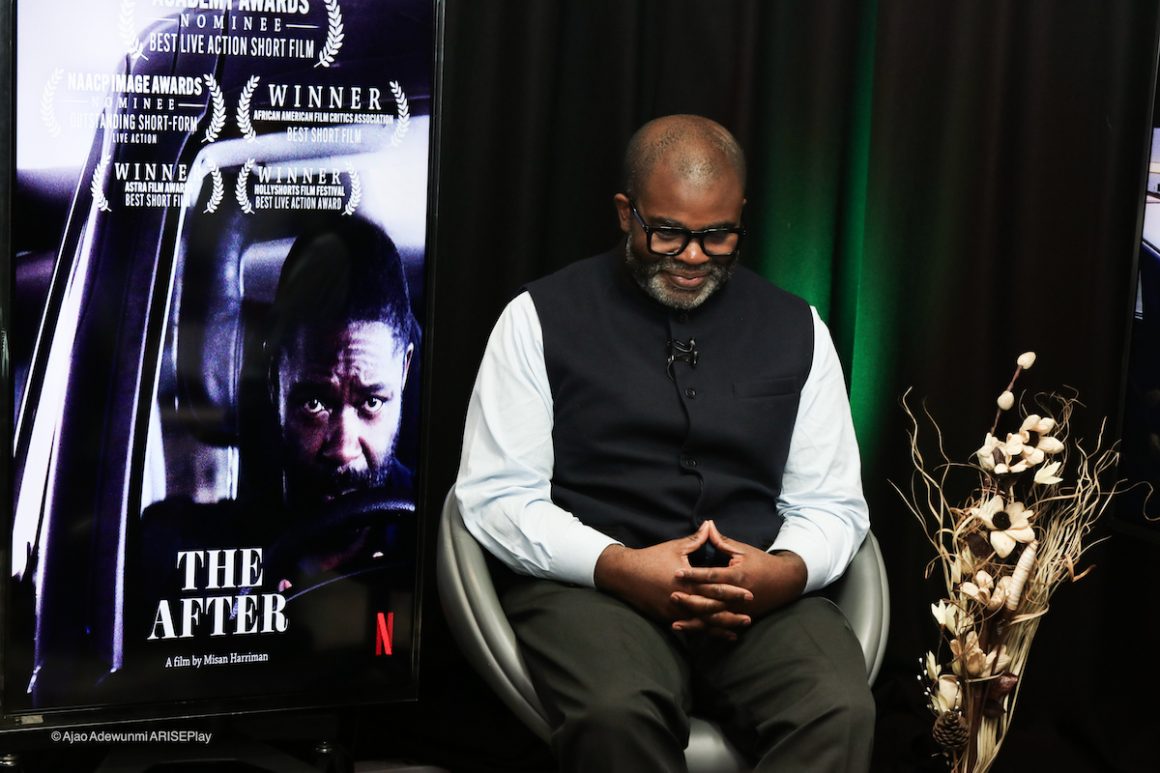

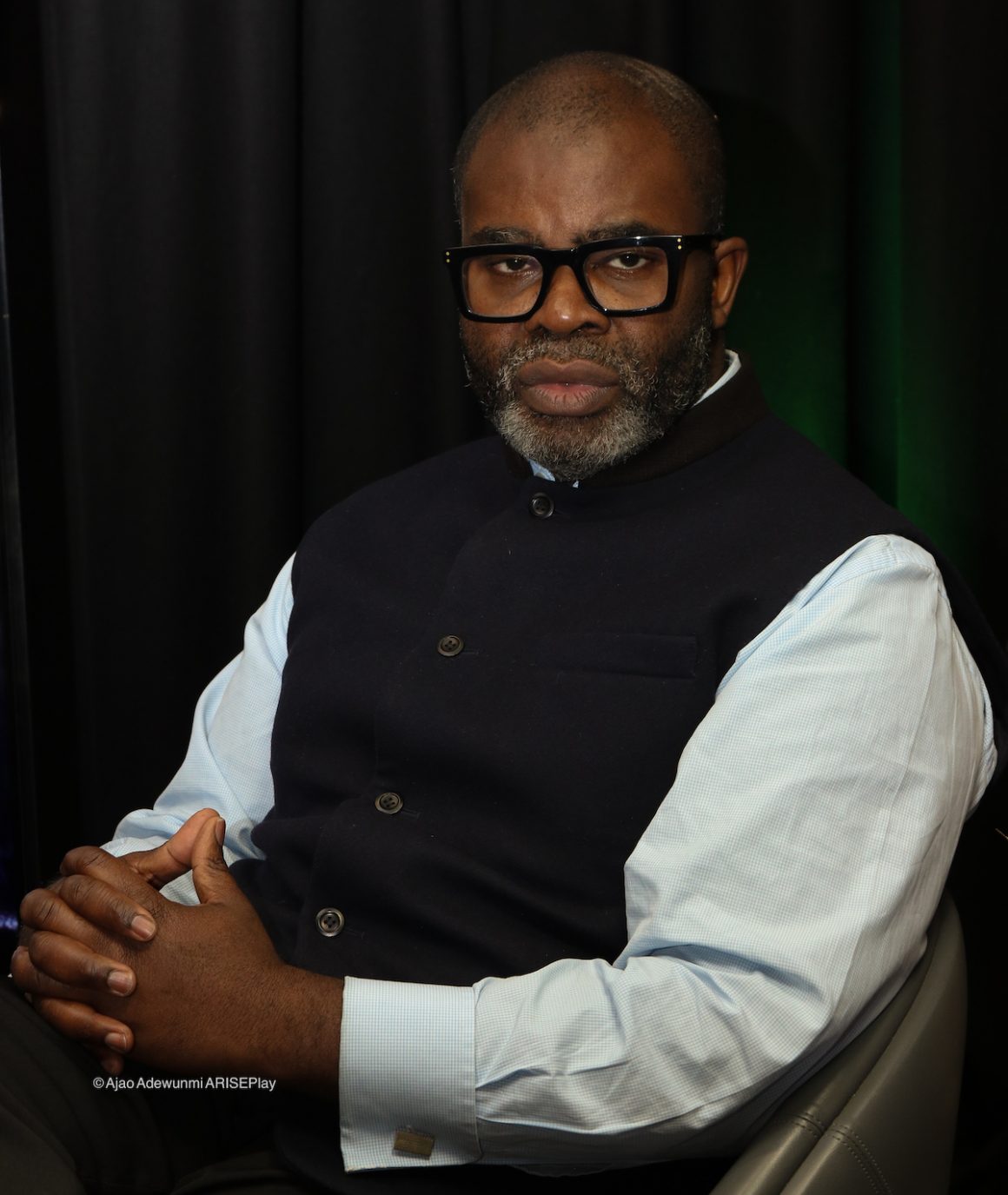

As Lily takes to the red carpet of the Oscars on March 10, hers will not be the only historical walk down that crimson runway of stars because experiencing the very same momentous rush of achievement will be a Nigerian Itsekiri movie director and writer named Misan Harriman, who with his first ever film, ‘The After’, has become the first Nigerian director to be nominated for an Oscar, the first Nigerian director of a short film to be nominated for an Oscar, and the first Nigerian director of a film starring a Nigerian lead actor, David Oyelowo, to be nominated for an Oscar. With so much shouldered by just one man, ARISE News correspondent Judita DaSilva interviewed Misan in London to gain some insight into his own personal perspective of his success.

Photography: Ajao Adewunmi

Misan Harriman, firstly, congratulations on the film and the success it’s been having. We can see some of those credits on the posters now. So, let’s go to the beginning. It’s your first film, your first short film, and it gets nominated for an Oscar. How does that make you feel?

You know, we don’t always believe that we can and should do certain things, and for a long time, I was just a fan of film and filmmaking, and there was never really a part of me that was strong enough to believe that I would be able to have a point of view. So to sit here with you, and they’re telling me this—this is Oscar-nominated—is genuinely beyond my wildest dreams. Which is why, when I watched it with my wife, they said, Oh, come to the academy building. I said, Why? So I should collapse in front of everyone? No, I was just on my sofa, and it’s funny because I knew it was in alphabetical order, so if they said any other film first, we were out. I just knew that. So when the person said ‘The After’, I couldn’t speak; genuinely, the brain told me to open my mouth, but I could not speak. So yeah, that’s how it was.

So in the film, we can see stars like David Oyelowo. How did he come on board with the project?

I’m shaking my head because I don’t know if I’ve met anyone in the industry like David. You know, with us, the collective is sometimes there. We see our idols, and then when we meet them, we’re like, damn. I already had a very high regard for this man, but he surpassed it in every way because he saw in me what I maybe refused to. He gave me the space to be a rookie filmmaker with a veteran—one of the great acting talents of our time. You know, I DM’d him on Instagram, and, you know, he rarely checks his DMs. David is a man of the Bible and a very religious man. Something made him look that day, and he saw this boy taking nice pictures, and he replied, “I love your pictures, and we should talk.” The rest, as they say, is history. This man believed in me. Before I even had a script, he was in. He was in. Wow.

So then, how did Netflix jump on board?

With Netflix, I had gotten to a place where I was very visible, and there were rumours that I wanted to get into moving images. So, there were discussions with other similar companies and TV channels. Misan is thinking of being a filmmaker, and then Netflix came in. We pitched them, and they made a really, really smart offer that would allow me to basically be able to shoot this film at the quality that a feature film would have in terms of DOP, the amount of extras I could have, the location scouting, all of that. I couldn’t say no to that sort of opportunity.

So you directed it. You wrote the story; then, the story was adapted to a screenplay by John Julius Schwabach.

Yes. Who’s part-Nigerian as well. Ah, yes, oh.

So, the story itself is quite traumatic. So why was this the story you wanted to tell and tell it this way?

You know, I think it’s a tapestry of some of my own personal experiences of unexplainable loss. Yeah. Many of us. We are also grappling with losing our dear Anthony, you know, in the bombings and in London. A bit of that was in there, I’ll say that. We were also thrown upside down by this act of God, COVID. Yeah, the pandemic was the only time where it didn’t matter who you were talking to or who you WhatsApped; you knew that they were struggling. You knew they were trying to reprogram their minds, like, “What is happening?” And then George Floyd was killed, and then all of those traumas of existing as a black person started climbing out of us. So I think it’s the losses of those we love and the mental health challenges of a world that’s seemingly on fire, and I wanted to put that on the screen so people who are struggling can know that it’s OK not to be OK. It’s OK to have invisible wounds, and we can try and build ourselves back up brick by brick because, again, culturally, I don’t think with Naija people we recognise mental health in the way that we should, whether it’s our aunts, uncles, mothers, friends, colleagues, or partners.

On the face of it, a short film seems simple enough, but cramming the totality of a cohesive narrative into 15 to 20 minutes is very challenging. Many directors I have spoken to have said, “It’s not until I started that I realised, oh, I don’t have enough time. Should this have been a feature-length film?”. How did you know you could execute in short film format instead of feature-length?

I think as a photographer, and when we storyboarded it, I had every single scene in my head with breathing room because I knew that with someone like David, giving him the latitude to do what few people on this planet can do with the kind of guardrails of the narrative arc, we would, if we got it right, get lightning in a bottle, but you’re right, it’s very untraditional. For example, the film starts with a crescendo. It starts with, “Oh my God!” I wanted that, and many people—friends, you know, people that I really respect in the industry—said that’s not how you’re supposed to do filmmaking. You’re supposed to lead people, and then you hit them with something. I said, “No, I want to hit them with something at the beginning because I want them to sit to attention and recognise it.” Although it’s 15 or 18 minutes, this is not something they’re going to forget anytime soon, and I wanted them to root for this man for the majority of the time that they had with him, and I couldn’t do that at the halfway stage. Yeah, and I also wanted them to understand the totality of his loss.

So, looking at your career, you have established yourself as a very well-respected photographer worldwide, and when you look at the transition, how did you know, having ensconced yourself in this medium, that “I think I’m ready to become a movie director now”?

Self-doubt is a hell of a thing, right? And I think for most of my life, it’s been self-doubt that has held me back, but the thing about opportunities is that when you enter rooms, and you start meeting the people who do the things you wish you could do, you see that they are human beings just like you.

You look back at your life and realise that film has been singularly the biggest influence in all your passions. You know, all I ever did was play video games and watch movies my whole life.

And there’s a great Robert Frank, the photographer, quote: “The eye should learn to listen before it looks,” and my eye has been listening my whole life. I mean, I was a guy who would bore anyone who wanted to talk about scenes in movies. I gave a talk at school, as a 9-year-old, about the lighting in Kubrick’s ‘Barry Lyndon’. So, I am that guy. So the irony is that, just like with photography, when someone put a camera in my hand very quickly, the quality of the work was quite high. Yeah, because although the object is put in my hand, my eye has been training itself really from birth, and that’s why, compositionally, even in this shot you see here [looking at the poster of his film projected on the TV screen], I remember telling my DOP exactly what lens we needed and what time of day we needed to be there, and we got the shot you see now. So there are some things, and I haven’t been to any film school; I dropped out of university and had terrible grades.

I think for the Nigerian parents watching now, it’s OK. Everything worked out. Everything worked out.

You know, it’s so important for me to say this, and it is being shown in Nigeria because, you know, everyone’s different. You know, I’m neurodiverse and dyslexic. I can barely spell and struggle in the traditional educational system, but I’m a visual learner. I taught myself how to take pictures on YouTube. I’m arguably the most visible photographer on the planet today. Right when many people looked away from me and said, “Oh Lord, he’s slow, he’s this, he’s that,” and I am all here today, so I’m telling you, don’t! If you have children who are struggling or are different, don’t lambaste them. Don’t look down on them. Find out why their mind is different, and you may see something extraordinary within that mind.

But now let’s speak about you being Nigerian. Your father was Itsekiri, and when Delta State heard the news that you had been nominated for an Oscar, they jumped to action. My mother is Itsekiri, and she was saying, “Listen, we don’t play. Now one of our sons is representing; we don’t play.” But you went to school in the UK, worked in the UK, and worked around the world, in Europe, and in America. How does it feel to know you still have recognition and support back home like that?

It’s everything. David and I have cried many tears because, finally, you know, he’s never been directed by a Nigerian man before. This is someone who was in ‘Interstellar’. He’s been directed by Christopher Nolan, but there were so many times when making this film where I would give him a look, and we knew there was no need to speak. We knew what it was. I felt like we had met each other in another life, and that’s why the trust he gave me, and hopefully I gave him to be this vulnerable, is what people are receiving when they see this film, and of course, when we wrapped, we had Naija food for everybody. I couldn’t get Banga soup. It was hard, but we got what we could.

Let’s circle back to your photography. You’re no stranger to making history because you were the first black man to shoot the cover of British Vogue, and at that time, it was 104 years before that happened. You are one of the most widely circulated photographers worldwide for the Black Lives Matter movement. Do you ever sit back and then get a bit overwhelmed, because especially as a black man, a black African man, the more heights you scale, like Denzel Washington has spoken to it, the more pressure comes on your shoulders because you’re now the shining light and everyone’s following your lead? Do you get overwhelmed?

With the Vogue one, I was so green. I was like, “What is going on?” And then it just went crazy, you know? It was really unusual because I describe myself as the love child of Gordon Parks and Cecil Beaton because I’m so known for celebrity portraiture.

Also, I’m at the tip of the spear of almost every civil rights movement I can get involved in, but the one I had to balance was when I became the chairman of the largest cultural institution in Europe. I’m chair of “Southbank.” I oversee 11 acres of London, from the tip of the London Eye to the BFI Southbank. I host the BAFTAs. I mean, we have the Royal Festival Hall and the Hayward Gallery all within that purview. I’m certainly the first person of colour to oversee anything like that, and it’s a government appointment. That one was crazy because I remember getting a phone call from a headhunter. I was in my kitchen, and he said, “Oh, uh, someone’s given us your name. We’re doing a recruitment search for the next chairman of the Southbank”, and I’ve been going to the South Bank Centre my whole life. I was like, to this guy, “OK, look, I’m not Lord or Lady so-and-so. I’m not in my mid-to-late-60s. You got the wrong guy,” and then my wife said, “But you love that place, you love that place,” and it represents the democratisation of art. It’s the most inclusive cultural space in Europe. I was like, “Yeah, but, you know,” and she goes, “Just attend the interview,” and 170-something people later, I was down to the last three people, and then the Arts Council and the board of Southbank made the historic decision to offer me the role as chairman of this insertion. That one…

Shook you to the core?

I was confused if you want to know. Out of all those things, it’s a great honour, obviously, but I’ve learned I struggle with anxiety. I still have anxiety attacks. I struggle with self-doubt, but there’s a great quote by John Steinbeck in a letter he wrote to his son after his son was heartbroken, and there’s just this line where he goes, “Nothing good gets away.”.

We should recognise that our challenges may lead us to the places that we end up being, you know? So that’s what I try to do. Also, I have two children who really don’t care. So they’re like…

Another thing I wanted to touch on is that you’re also the first official black photographer of the Royal family, with the images you’ve done of Harry and Meghan, Princess Beatrice, and Edoardo Mapelli Mozzi.

Yes.

Being a black person in that space, that’s seen as kind of the hallowed halls of white supremacy, not in any negative light. How do you navigate that space? Because, as you said, Cecil Beaton and all these photographers laid the tarmac for what it should be, and then Misan Harriman comes?

That’s crazy. I mean, a lot of people don’t know the timeline of my relationship with that household, but, you know, I shot Princess Beatrice’s engagement pictures in the Royal Lodge, which was the home of the Queen Mother. It’s where Princess Beatrice and her family live, and that was where Cecil Beaton took some of his most iconic portraits, and he’s always been an idol of mine. So when I walked through that garden with my camera, it was again, “What is going on?” … and the Queen was very much aware of those images. She was still alive then, and, yeah, it’s very hard to process again, but I always focus; if I’m confused by something, I focus on my job as a photographer and the kind of images I take. I know that when I’m long gone, when my children have grown up, they’ll say, “Oh, OK, he wasn’t that useless, this father of mine.”

I spoke to a friend of yours, and they gave me an anecdote that they can remember of you in your 20s, back when they had the early camera phones, that you’d be at parties and social gatherings, and they’d be having a conversation, and not until way into the conversation, they’d notice that your hand was out of sight with the camera open, taking pictures because you like the candid image, just them in their natural state. So, obviously, the passion was there. You didn’t have the machinery yet. Then you went on to curate a mind-blowing collection of global images by the widest variety of photographers with your company, ‘What We See’, that took off. Then your career as a photographer burgeoned, and now you’re an Oscar-nominated director. As Nigerians, we know the idea that “it’s not necessary; just do it.” Speaking to how diligence, dedication, paying your dues, and taking steps yield greatness.

I would say this: I failed, and I failed, and I failed, and I failed, and then I failed. Until, one day, I didn’t. I believe greatness in your own story is what you do in the moments between giving up. Between failing and giving up. In the moments where we are in that dark place where it seems like there is no light, in the opportunity of our human story, I think that’s when you can carve out the version of yourself that the world will see. When I started taking those pictures of Black Lives Matter, an anti-racist movement, I didn’t know what else to do because it was lockdown. I felt drawn to hit the streets. My friends were very worried because it was during the COVID pandemic, but I said, “I have to do something,” and at the time, I had, like, I don’t know, 800 followers. I wasn’t some hugely well-known person, and I remember shooting these images, pinning them on my Instagram, and waking up a week later. I couldn’t open my WhatsApp because I was getting so many notifications, and the son of Martin Luther King had somehow seen my images.

Now, one of the reasons I started loving photography is because of an image of his mother, Coretta Scott King, at the funeral of Martin Luther King, Jr. So, for the son of Martin Luther King to see my photos. He didn’t even know they were taken in London. He must have thought they were taken in America because he posted them on his [social media], and then someone told him there’s this guy. So he then tagged me, and then everyone—50 Cent, Puff Daddy, Kanye—were all sharing my images. That’s how it really happened. It was completely organic, and I’m sharing this with you because you never know when the universe is going to see your work. I didn’t have an agent. I didn’t know anyone at Vogue. I didn’t. I was just walking the streets, and the camera I was using in those days wasn’t anything special. I was just taking my own little bite out of life. So that’s number one. Number two: celebrate the small wins. I first got a camera—a real camera—for my 40th birthday from my wife.

I took such terrible pictures on holiday, came back, and started going on YouTube, and every time, I started learning about aperture, shutter speed, and ISO; those, for me, are the big wins that have brought me to this place here. It’s recognising the little wins that lead you to a place of, I would say, recognition. That’s as important as any other part of the journey, but embrace your failure because it’s leading you to a place where failure will be only a distant memory.

Well, my final question is the one you already know everyone’s going to ask you. You posted that video on Instagram of when you and your wife were in the living room watching the nominations being read out, and then your category came up. Yours was the first name read out, and you were speechless. Like you said in the caption, you just couldn’t speak. The night comes in March, and if they read your name out again, how do you think you will react?

I genuinely hope I don’t faint. There’s a strong chance I could. I could actually hit the floor. If, by some miracle, that doesn’t happen, I will try to articulate how important it is for us to love ourselves. We have always been enough. We really have, and that’s what this film is about—healing and recognising that you are enough and deserve existence and a point of view in this, with whatever we have. God knows how long we have left on this earth, and I think if that does happen, I will try to articulate that without sounding like a mumbling child, and of course, I will thank everyone who has seen me and given me this journey to make this film.