I recently had a sit-down with Igunma Osa-Jean, affectionately known as “Jay” by his inner circle. He is the visionary behind “Olode and Thread”, a celebrated fashion brand that seamlessly intertwines tradition and modernity. Our meeting commenced over a delightful meal at The Lobby Bar of The Borough, followed by a tour of his store and office within Lekki Phase I. Here, I had the privilege of personally engaging with the pieces from his upcoming traditional wedding collection, “Forever”. I was impressed by the impeccable craftsmanship and attention to detail that permeated each creation.

Jay’s effortless charm and affability fostered an environment where conversation flowed seamlessly. We delved into his earlier days, unravelling the threads of his journey into the fashion industry and discovering the fusion of passion and purpose that propelled him to the forefront of Lagos’s fashion landscape.

Despite being a well-kept secret for a substantial period, Jay expressed his readiness to embrace the limelight, affirming his resolve to share his creative prowess with the world. Having had the opportunity to dress famous personalities like Bovi, RMD, 2Face Idibia and more, he is just beginning his journey, and we are excited to see where he goes next.

What sparked your interest in fashion design, and how did your journey as a designer begin?

There were plenty of things I dreamt of becoming as a kid, but a fashion designer wasn’t one of them. I would say I inherited my love for fashion from my parents. My mother loves clothes, and I recall my father hanging a shoe rack on the wall with rolls of shoes that went around the length and breadth of his room, maybe twice—those early days inadvertently made an impression on me. Professionally, the decision to become a fashion designer was a clear case of necessity, being the mother of inventions. When I was about 9, I recall my mother taking me to tailors to make me gabardine outfits because that was in at the time. I haven’t gotten over the memories from that Christmas, and it wouldn’t be until decades later that I realised what had happened to me; fashion had adopted me without my consent. In my late teens, I needed an outfit made, and it was at the point when, as a young boy, you had managed to convince your mother that she didn’t need to buy your clothes anymore. If she was nice enough to hand you the money, you could do your thing. Probably because she had recently given me a belt that was twice the length of my waist. It was my first time getting traditional outfits made by myself, and unfortunately, it wasn’t as easy as I imagined. I spent weeks scouting tailors and finally settled for some dude who made me this horrible outfit. At that point, I realised how difficult it was to access proper tailoring services, although I didn’t delve into the business at that time for that reason. I still wanted to become a doctor, and I thank God that idea didn’t work out. I was a huge music lover, and I collected American music and fashion magazines a lot. Vogue, GQ, Vibe, Source, Complex—you name it. That gave me massive exposure to what was going on in the fashion industry, which, at the time, was closely associated with American hip-hop culture. I followed the brands keenly, and at some point, I was so fascinated with the sneaker culture that I started sketching sneakers. Considering it was next to impossible to design sneakers locally, I mean, back then, the world wasn’t as connected as it is today. Now, you can go on Instagram, speak with some guy on the other side of the planet, and have a prototype of your merchandise shipped to you in a week and a half. Then we didn’t even use the internet like that. I had to settle for what was doable at the time, and that was designing and making leather slippers. That was how my journey began as a fashion designer.

What motivates and drives your passion for creating fashion?

People. I soak up a lot of energy from interacting with people, and I don’t force things. I don’t try to create hit pieces. I try as much as possible to attend to what’s in front of me as best as I can. I like to go to stores A LOT—you know, malls and convenience stores. I think commerce is one of the purest forms of human interaction, and I enjoy watching people relate on that level. I like to think I am quite customer-centric. I mean, you can’t please everybody in the world, but as a designer, trying to do that with your customers will get you very far. It’s the reason why word of mouth was my biggest advertisement for years, to the point that it almost felt like I was the best-kept secret in Lagos. People take my work very seriously, and it’s my duty to outperform their expectations. That is one of my biggest motivations.

How would you describe your design aesthetic in three words?

Simple. Sophisticated. I’d say “Timeless”, but Davido beat me to that one.

What inspired the name “Olode and Thread”?

Olode is an Edo word for ‘needle. Essentially, my brand is called ‘Needle and Thread’. When I started out, due to the influence of hip-hop at the time, there were a lot of graphic t-shirts and the like. People called themselves designers just because they came up with some fancy phrase and printed it on a blank t-shirt. Personally, I thought those were trying times for fashion as a whole because there wasn’t much attention to detail, and the craft suffered immensely. What we did was different. It required more artisanship and depth, and I needed a name that captured the essence of that since I didn’t want to create an eponymous label. Before that, I had come up with some really horrendous names, which I will not mention today, not even under duress. ‘Olode and Thread’ felt and sounded right, and I was particularly enthusiastic about the fact that it had an Edo word in it.

Which would you say you enjoy more, crafting clothes for men or women?

Working on women’s clothing is, of course, more challenging. With men, it’s straight to the point: good fabric, a pristine cut, clean seams, and you’re almost home and dry. You know all that stuff they teach you in fashion school? You need every last bit of it when you make women’s clothing—you gotta clap, sing, and dance, so to speak. At some point, I would say I got bored making menswear. I noticed a lot of things I could do differently with women’s clothing while I was making menswear. Many of the details I noticed were tacky, and I wondered why people didn’t approach it with the same level of attention to detail as I did for men’s clothing. You can’t tell if a meal is sweet by watching others eat it, so I had to dig in. It was what inspired the idea of getting into womenswear. You have more opportunities to showcase your creative prowess with womenswear.

What inspired your latest collection? Why did you decide to go with traditional wear?

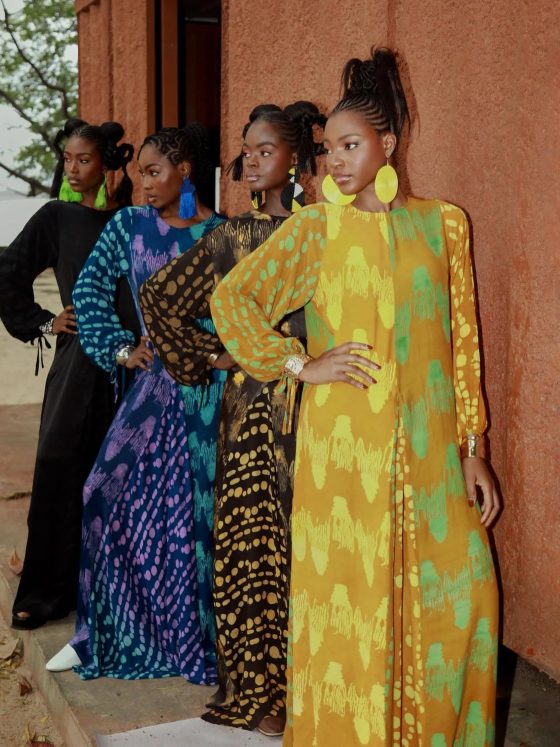

Love. You can’t marry every day, but you can be a part of people’s love stories as many times as you wish if you design the clothes they marry in. We had our last womenswear collection a while ago, the ‘One of One Collection’. I thought I’d up the ante by doing something different and more intense. It had to be a traditional wedding collection. My money says it beats suits and white dresses any day. I think you have more untold stories in that space. Culturally, we are very diverse, and I did what I could to reflect that in my collection. Why would anyone pass on the opportunity to show off an Edo bride? Hopefully, a Western wedding collection is on the horizon, but home is where the heart is, and charity begins there, I hear. Plus, there’s already a deluge of Western-style wedding collections worldwide. There are plenty of people telling that story, but it’s just us telling ours. I like to take my time; doing both in this collection would’ve taken forever.

How would you say this collection reflects your personal journey as a designer?

It’s been 20 years since I started out. The thing with being a fashion designer is this: every day, you learn and build yourself as you work. Every experience is registered inside of you, brick by brick, almost like you’re building a house you never finish. It’s the reason you find more old designers at work than singers or athletes. The work we put out doesn’t diminish us; rather, it enriches us and equips us to be better at it. This collection is the culmination of everything I have done so far. A summation of all of my experiences, my fingerprint, and everything that makes me special.

What do you hope people feel when wearing your designs?

For starters, I hope they feel comfortable. As a designer, I have heard people repeatedly say there’s this thing about my work—that even when they look remarkably simple, there’s something they can’t put their finger on that does it for them. I tell them it is the fact that I have a piece of my soul in all of my work. The ability to anticipate the needs of the people we serve before they know they have such needs is what makes us the greatest servants. If you really want to see how confident people can get, dress them up very well. It’s not just something I hope people feel, but something I have seen happen often.

I hope I can help people express themselves. That is extremely important to me—to make clothes that, if they were songs, would be the soundtrack to people’s lives.

What do you hope to achieve with your designs on a broader scale?

Hmmm… how about we start with a few billion dollars? Lol. I mean, considering this is my day job, that wouldn’t be a bad idea at all. There’s a lot of work to be done. Fashion is a very prominent, albeit small, part of design. In the time I’ve been a designer, I have been able to make the switch from being a leatherworker to a menswear designer, and then I combined womenswear with that.

As diverse as that sounds, it’s still all within a subset of fashion in itself. Ultimately, we would like to go the long haul and spread our offering across the entire stretch of fashion, be it menswear, womenswear, childrenswear, footwear, accessories, and all of that.

Lastly, what legacy do you hope to leave through your contributions to the fashion industry?

It’s still early to talk about legacy, but I hope to leave this place more organised than I found it. Take footballers or musicians, for example. Some 20-odd years ago, people wouldn’t let their kids aspire to be footballers or singers. Those dreams were for the dregs of society. Fashion in Africa is very similar. Then great minds like Jay Jay Okocha and 2baba happened, and now you have rich people scrambling to send their kids to soccer academies and music auditions. Our industry is still some sort of diamond in the rough. It has all the potential to shine, but we have to be willing to put in the work to polish it. I am very conscious of this and believe it is my responsibility to ensure the ultimate outcome is achieved.