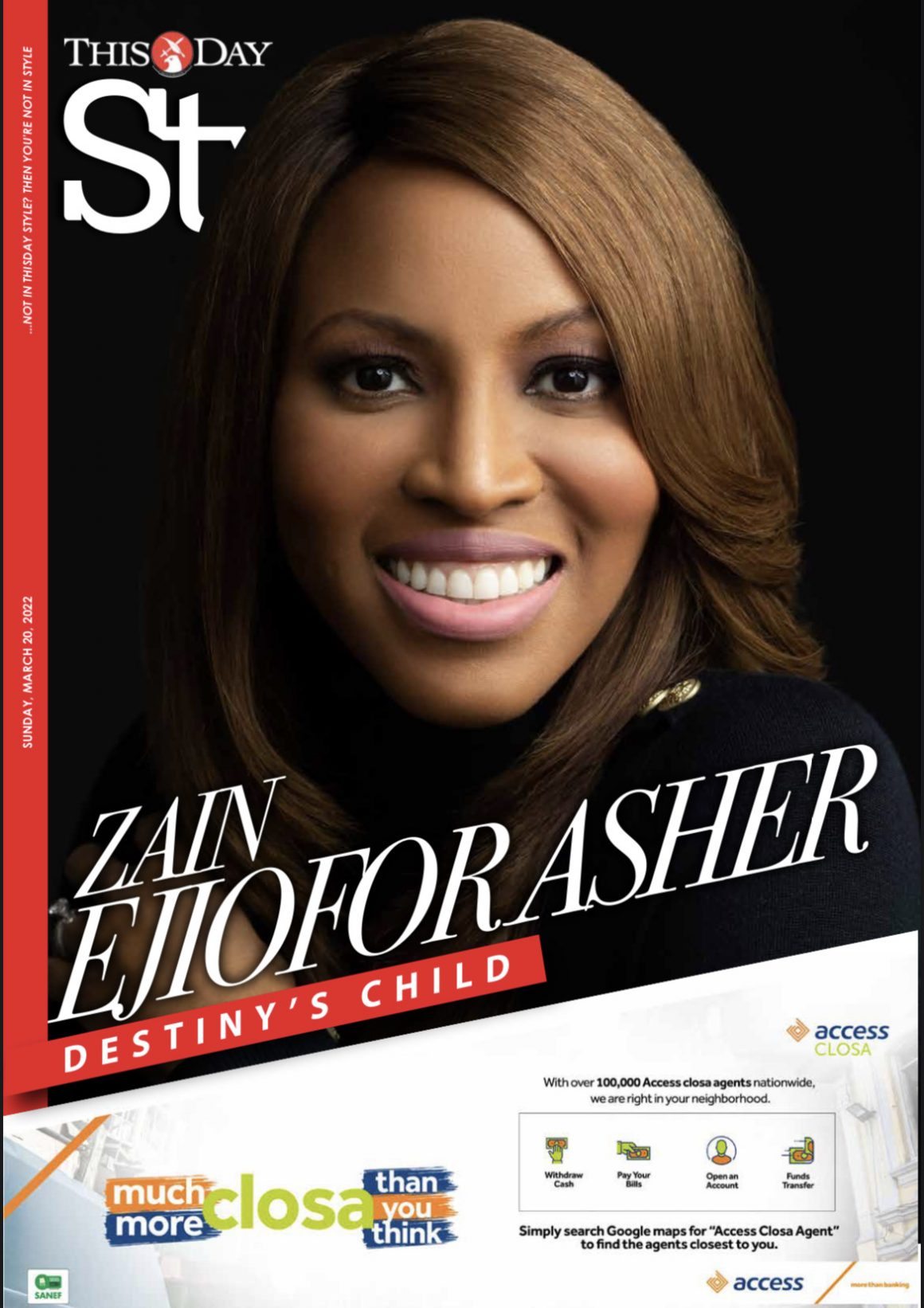

In her book, Where The Children Take Us, Zain Asher talks about how her family achieved the unimaginable. This spellbinding story opens up with a woman receiving life-changing news that her husband and son, Zain’s brother Chiwetel, (the only survivor of the crash), have been in a terrible accident. In that instant, she becomes a single mother left to raise four children in a South London neighborhood consumed by poverty and violence. Zain says there is tragedy in her story, but her story is not a tragedy! These poignant words ring through as her mother’s fierce parenting style produces an Oscar-nominated actor, Chiwetel Ejiofor and a recipient of an OBE from the Queen of England, an Oxford-educated CNN anchor, a medical doctor and an international entrepreneur.

The dogged determination and discipline Zain’s mother instilled on her children made them what they are today. Under her guardianship, they grew to learn the rudiments of life and became successful in their various endeavours. The story paints an unforgettable portrait of strength, tenacity and love. It’s a testimony of the sacrifices Nigerian parents make to raise successful children.

After graduating from Oxford University, Zain bought a one way ticket to attend Columbia University because halfway through Oxford, she had decided she wanted to become a TV news reporter as the idea of being thrust into new environments thrilled her. Five years into this foray, she was still hopeful for a big break. Nine months after holding light reflectors for!a friend at her own gig, Zain got her dream job as news correspondent at CNN. Raised to believe a victory for one is a victory for all, Zain did not rest her laurels and instead pushed further to become an Anchor with her own live show, CNN’s One World With Zane Asher. Funke Babs-Kufeji reports…

What challenges have you faced in your high-powered position and how best can you advise women to use their sphere of influence?

I wasn’t always a CNN anchor. After college, I actually worked as a receptionist for more than three years. I worked hard to get promoted, and it just didn’t happen. I know what it is to struggle in my career, so now that I am in a better place at CNN, I’m very conscious of using my sphere of influence to help other women who may be trying to climb the ladder like I did. I try hard to be responsive when people ask me for career advice, I mentor other women, and I generally look for ways – big and small – to give women opportunities they otherwise may not have had.

Nigerians have a very high percentage as the most educated group in the US regardless of the daily challenges we face at home. Why do you think this is so?

Nigerians have an inherent drive and resilience that’s rare in this world. This is one of the main themes in my book, “Where the Children Take Us.” I’ve spoken to so many young people in Nigeria who tell me that doing business here can be a battle. There’s so much bureaucracy and red tape and the energy crisis poses a major challenge. But they continue to fight — and many succeed. So when these same Nigerians are placed in the U.S., where the daily challenges aren’t as intense, of course they soar. There’s no stopping us. As I write in my book, “Survive in Nigeria and you can survive anywhere. Thrive in Nigeria and you can change the world.”

Some would say on CNN, Africa is most times, constantly undervalued and underrated. Do you feel there is a robust enough representation of African women especially, in the global media?

My show, “One World with Zain Asher,” is actively working hard to address this criticism directly. Our goal has always been to democratize news coverage to make sure that Africa has an equal seat at the table compared to other parts of the world. I have a segment on my show where I explain what’s happening in Africa in a way that ensures people watching from any city in the world, Prague or Brussels or New York, understand that what happens in Africa affects them. There’s always room to improve, but I’m very proud of the work we’ve done so far.

How are you using your voice to highlight unsung heroes?

I make a real effort to highlight unsung heroes on my show. My hope is that by helping to amplify their voices, they can inspire many others. One of my favorites is Angela Murimirwa, who is working to implement something called “social interest.” The idea is that when women pay back a loan, instead of paying back the interest with money, they repay with service — things like supporting other women, mentoring, teaching. I think it’s a fantastic idea to transform communities by lifting each other up.

The death of your father at an early age, left your mother with three kids and pregnant with her fourth. What do you think saw her through and helped her overcome what surely must have been the darkest moment of her life?

My father and my brother were on a road trip in Nigeria when their car collided with a tractor trailer. My father was killed and my brother was badly wounded. In that instant, in September of 1988, my mother became a heart-broken, widowed immigrant with little money and little hope, living alone in London. I know now that she found a way to fight through her hardships because we Nigerians are fighters, if nothing else. My mother came of age during the Biafra war where she had to fight through ethnic cleansing and bomb blasts and starvation. She overcame horrors as a teenager I cannot imagine. So when she faced the horror of my dad’s death, she knew that as hard and as painful as it was, she could, eventually, overcome that, too. Despite her agony, she carried us on her back to give us a better life. And thanks to my mother, my siblings and I have managed to defy almost every expectation. I’m now an anchor at CNN, my brother was the first African to be nominated for an Oscar for Best Actor, my sister is a doctor and my oldest brother is a successful entrepreneur. We overcame because she showed us how to.

As children, you said your mother’s life lessons extended far beyond the classrooms. What commitments did she make towards your academic futures?

My mother gave everything she had to our academic futures. She plastered newspaper and magazine articles about Black success stories all over our walls to show us what Black people could achieve. She taught herself Shakespeare when my brother started acting to push him to be better. When my grades started slipping, she literally cut the TV cord in half and installed a residential pay phone to keep me focused on academics. I would have nothing if not for my mother.

What preparatory steps did you and your mother take years before you got admitted to Oxford and how did you feel when you finally achieved this feat?

My mother started taking me on mother-daughter road trips to visit Oxford University when I was 13 years old to help me believe it was possible for someone like me to go there. It became a tradition of ours. We toured the buildings, learned about the different colleges and ate at local restaurants beside real students. She wanted to show me that Oxford was not some mythical place. It was within my reach. The more I visited, the more comfortable I felt there, and the more I realized that going there wasn’t some crazy dream. She made it real for me, and so it was.

You got a place at CNN only two years after being a receptionist. What extra measures did you take to ensure this dream also became a reality for you?

I figured that the quickest way to get a job in broadcast news—at CNN or any other news network—was to have a specialty or some area of expertise that could help me stand out. That could have been sports, entertainment or politics. I’d studied economics for A-level and loved it, so I decided Business News would be my specialty. From then on, I spent every spare moment at the library studying stocks, bonds, derivatives and mergers. Eventually, that was enough to get an entry-level reporting job at Money Magazine, which was owned by the same company as CNN. And when CNN wanted to expand its business unit, I was in a position to get their attention, even without extensive broadcast news experience. I may have been in the right place at the right time, but I also worked hard to make sure I was prepared when the opportunity arose.

Who inspired you the most and what role did the person play in getting you into CNN?

My biggest inspiration without a doubt was Femi Oke. She was one of the few Nigerians presenting the news when I was growing up. My mother would call me and my siblings into the living room to watch when she was on TV. She’s an example of what I describe as an “uplifter” in my book — even though she didn’t know it. When I was a young journalism student living in America, I actually tracked down her email address and sent her a note asking for career advice. Surprisingly, she emailed back right away and gave me her phone number. We spoke for more than an hour that day and kept in touch, so when I scored an interview at CNN several years later, she helped guide me through the process. Femi Oke literally changed my life, and her generosity set an example I try to follow even today.

You were a business correspondent for less than a year before you decided you wanted to be an anchor. At the time, it seemed like an unrealistic ambition as you were relatively new in your present job. How did you overcome the odds and fulfill your ambition?

One of the things my mother taught me was to “prepare in advance.” That meant my siblings and I rehearsed for what we wanted from life, long before the opportunities presented themselves. When I was in primary school, my mother would teach me my subjects a few months before we learned it in school so I’d be better prepared. And later in life, we prepared for jobs before they existed. I always wanted to be a news anchor. So, soon after becoming a business correspondent, I began to spend time each week practicing my anchoring skills with a former professor, even though there were no anchor positions open. He thought I was crazy. But when an anchor position opened up out of the blue, he was stunned. And I was ready.

What lesson will you like to share that has been critical to your success?

I’ve covered a lot already, but I’ll share one important lesson that may sound counterintuitive. Simply put, I don’t believe in competition. I’m not saying it doesn’t exist or that healthy competition doesn’t have a place. But I’ve realized that seeing other people as my competition, or comparing myself to them, can stifle my growth and keep me small. There is enough abundance in this world for everyone to reach their dreams.n my work and personal life, I try to wish the best for the people around me, even if some might consider them my “competition”. As my mother says, “Be your best, not their best.”