They went wild, hollering, “last last, na everybody go chop breakfast!” The dreadlocked performer turned his microphone to the crowd, the music stopped, and everything went quiet for a second. Then the sudden groundswell of “shayoooooooo!” rent the night air from the voices of 10,000 people. This wasn’t Tafawa Balewa Square or the Eko Convention Centre; this was last summer in Montreal.

That’s the phenomenon of afrobeats, Nigeria’s biggest cultural export in history, because of its sheer power and the immediacy of its impact on billions of people. From the taxi driver in Mumbai bobbing his head to CKay’s “love nwantiti” to Obama’s playlist featuring Wizkid and Tems, afrobeats boasts an imposing presence on every important chart one can think of, and heavy airplay on radio worldwide.

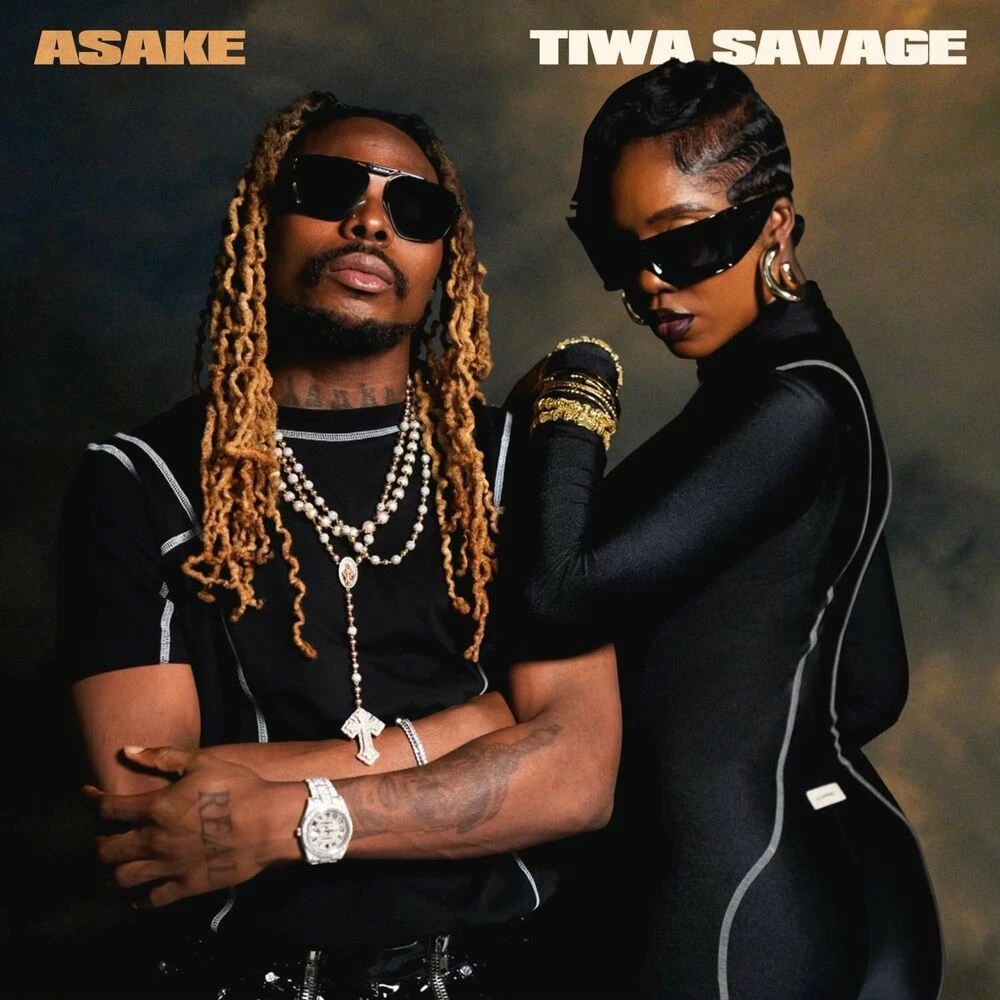

Several Nigerian afrobeats artists have had an outstanding year: Burna Boy, Wizkid and Davido topped the bill with sold-out arenas from Europe to North America. Tiwa Savage’s Water and Garri Tour had a strong showing in several European and US capitals. Electrifying performances by Rema and Fireboy have us all hopeful about the next generation of acts as they work hard to cement their influence on an industry driven as much by pop culture as by streaming data and dollars.

Only a few years ago, performances on the scale we have seen in the past two years would have seemed implausible, but an increasingly connected world and the instantaneity of digital experiences means that everything in the world is now happening literally at the same time on every continent. But is this enough for afrobeats to stand the test of time and trend, more than other forms of music that came before it? Going back to a time in the early 90s, when another global phenomenon called ragga-dancehall took over the airwaves. Most people who came of age during that time remember Shabba Ranks’ “Ting-a-Ling” and “Mr. Loverman.” They danced to Patra’s “Romantic Call,” and Shaggy’s “Mr Bombastic.” By the late 90s, dancehall’s popularity had begun to wane as it made way for the resurgence of hip-hop and RNB.

Again, soukous music was popularised by Awilo Longomba and made waves in Europe for a time. For the older generation, highlife and calypso was the rage that drove the 60s and the 70s. Today, they are vintage genres, treasured by a few but possibly awaiting a resurgence in the future.

Promoters of afrobeats contend that the music hits differently today, that 1972 and 2022 are widely disparate – a 50-year leap into a different dimension exposed to speed and technology.

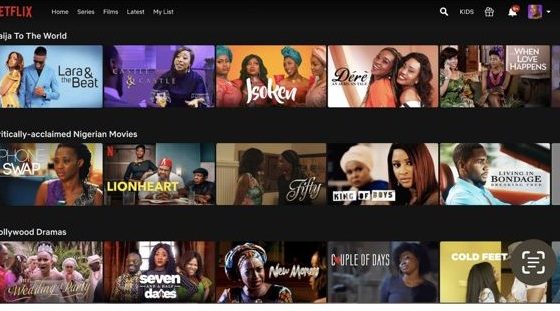

Today, afrobeats is categorised as world music, another term for non-Western music, or music not primarily based in the United States – or music that is not 100% English. Like calypso, soukous and samba music, afrobeats is not mainstreamed and is mostly seen as quasi-traditional. This means it runs the risk of being on the sidelines like other world music before. Therefore, a helpful approach to maintaining relevance has been features of mainstream pop artists like Justin Bieber, Brandy, Ed Sheeran, and others. Wizkid pioneered this move with Drake’s wildly popular “One Dance” collaboration. New York Times called it a transnational dance-floor lullaby, one of Drake’s breeziest and most accessible songs. Since then, a slew of songs has captured Western audiences, including future’s hit song “Wait for U” featuring Tems, which debuted at number one on the Billboard Hot 100 a few weeks ago. Accessibility to afrobeats by global audiences is key to its survival, and so is better coordination within the one-billion-strong African market. The success of K-POP and China’s C-POP stands primarily on their local audiences, who understand their language and can truly connect to the artist they call their own. If Africa can do the same, then we need not worry if the world’s attention turns away from afrobeats to the next iteration of gagnam style.