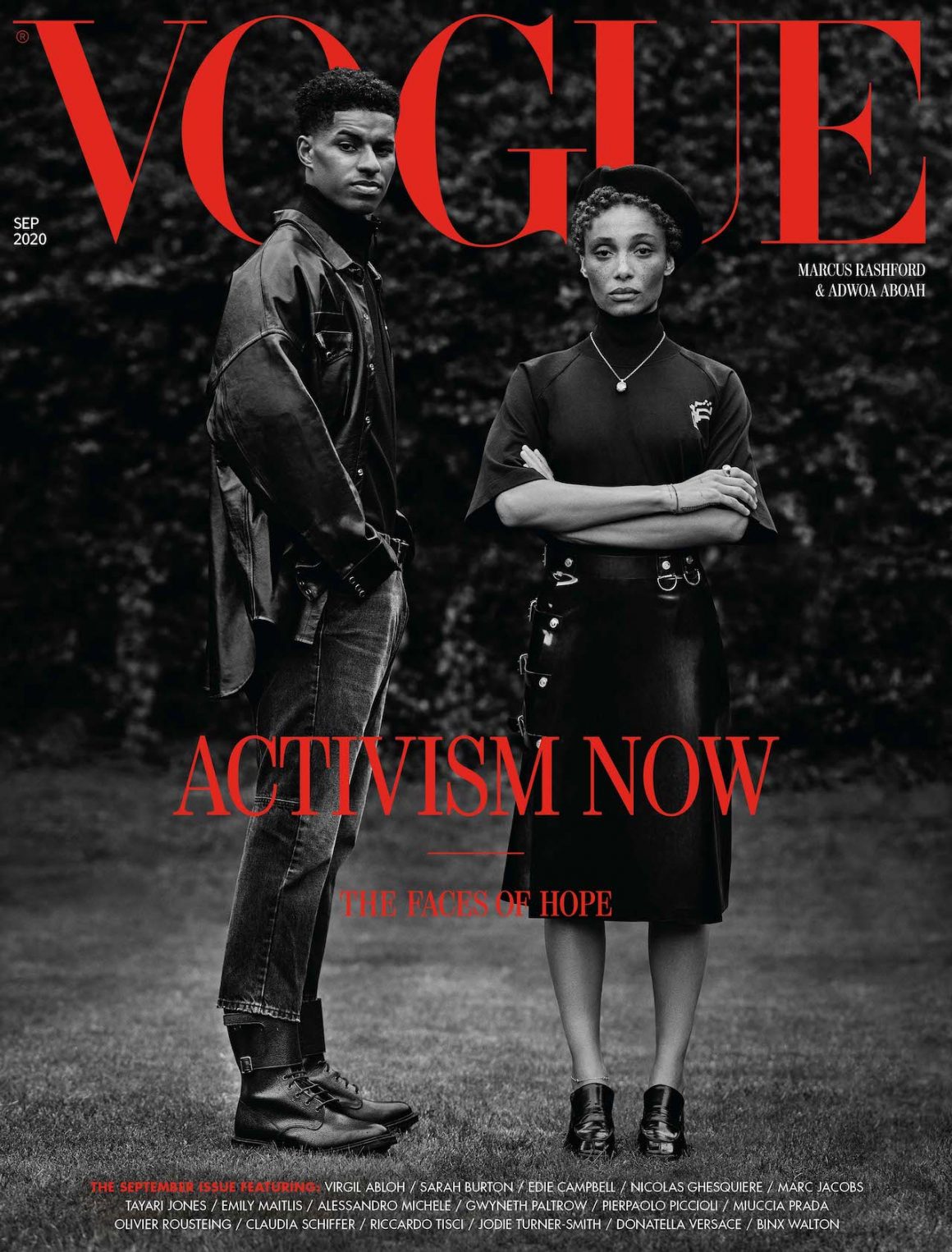

Misan Harriman made history by being the first black male to photograph the cover of British Vogue in its entire 104-year history. He founded a digital publishing company, What We See which reaches an average of 172 million people a month in 37 countries. Guest Correspondent, TUNDUN ABIOLA talks to the Nigeria-born and UK-based multi-hyphenate, photographer- content creator- content curator- cultural commentator about his work, his business, his family and why black lives matter. He talks about authenticity and how innate proficiencies; interests and traits form the building blocks for the formidable career he was born to have.

You’re in Sweden with your family now, you have your camera with you. Who or what are you shooting?

I’m shooting those that I love. That’s how I really learnt how to capture somebody’s essence and understand what to look for in my composition. When you’re shooting someone that is your world and your heart, there’s an intimacy you learn to pull out of an image that hopefully, I can replicate when I’m shooting other people.

You took an unconventional path into photography. You didn’t take courses or work as an assistant. How did you learn the techniques?

I’m pretty dyslexic and I’m incredibly visual in how my brain receives information. I watched a lot of tutorials on YouTube that teach you how to choose a camera, about shutter speed and understanding light. Anybody can go to YouTube. Any time I didn’t understand something, I found someone who had posted how they had fixed the same problem online. Then I got out there and started shooting. There’s only so much anyone can teach you about becoming a photographer. You’ll learn your skills “on the road”.

How did your Vogue cover come about? Who made the call and how did you react? It must be gratifying to not only have made history but to have made it your way.

The opportunity came about because of my anti-racist Black Lives Matter reportage photography that I had been shooting over the last three months. Those images went viral very quickly. Everyone from Martin Luther King’s son to Lewis Hamilton, the Mayor of London, Diddy, Sarah Jessica Parker all used these images to make statements about racism. Millions of people saw them and Edward Enninful, the Editor in Chief of British Vogue was shown these images. As a black man who has had the same experience as all of us, the images resonated with him very deeply. He posted some on his personal Instagram account and posted a few articles online. A few months later, I had a zoom call with the senior management of British Vogue and Edward. In his humble and very sweet way he just said, “I would like you to shoot the cover your way and how you like to do photography”. I did everything during the call to focus and not collapse or pass out!

I know the Vogue magazine and I know the importance of the September issue. It would have been extraordinary to get a cover but to have the September issue at this moment is beyond my wildest dreams. It’s a great example of how to use power.

Edward is the most powerful man in the fashion industry right now but he wields it with so much empathy. He has empowered me to now have a platform where hopefully, I can lift others up and that’s something I do not take lightly and will definitely try and emulate.

The September issue of Vogue has particular cultural significance more so now with the call, Activism Now.

What are your thoughts on fashion going political?

We have no choice right now. We’re talking about our lives and our babies’ lives. It’s the biggest stain on modern man. If you have a platform that people listen to, you have to use it to try and force change. Edward has experienced racism, so the cultural significance of this moment was everyone finally coming together to fight this thing. We never even thought it would happen.

That’s why the response to this issue has been so overwhelmingly positive. We needed to see a marquee, iconic brand saying, “We’re with you and we’re fighting alongside you to get rid of this awful thing that should never have existed anyway.

I’ve cried when I get videos of kids from working class backgrounds that have never even heard of Vogue who are taking their pocket money and going to Co- Op or wherever to buy that issue because it makes them feel that they matter.

Do you think there’s been a shift towards racial equality?

What happened in our parents’ and grandparents’ generation is that they could never mobilize properly because they didn’t have one thing and that’s the internet. The death of George Floyd was seen online, and it was like lighting a tinder box. We now know that there are enough of us that are against this horrible thing and there is no going back. That’s why I believe there is a change. When I was out in the protests, the biggest civil rights movement that the UK has ever seen. I saw 9/10-year olds boys and girls who were reading about the history of civil rights and racism. That gave me so much hope because I know that they don’t ever want to repeat the history that has been hidden from them. That’s when you know you’ll have real change when this generation knows what happened. They haven’t had some revisionist version of history like I had at school. They have empathy in their hearts, and they want to force change. That is as important as people who are in their 40s like me fighting for it. What I’ve seen in London has been hope and solidarity between people from all walks of life. That’s unexpected because in the London I grew up in, to have five thousand people of all races saying, “We’re fighting for people that look like you, Misan” has never happened before.

Never. It’s always been our problem, not theirs. You also chronicled life in lockdown, documenting the global pandemic in your project, Lost in Isolation. Again, serving as a witness to a seismic historical event. What do you aim to achieve through your lens? Do you have an overarching theme?

I want my photography to be a time capsule of the human condition and show who we are, unfiltered. The thing about the Lost In Isolation series is that it was a very difficult time for me personally like most people. The world was literally turning upside down. My anxiety levels were very high. I had just had my second child and did not know what the future held. The only thing I felt I could do was grab that camera and just observe. What I observed was that at a time when we were at our most vulnerable, we all came together. I never used to speak to my neighbours. It was always hi/bye on the commute to work but during isolation, we would check in on the older people that live near us and have conversations from afar. Strangely in this moment of solitude, we became more connected and that’s what my camera, I believe, captured. We know that we are lost in isolation, but we are found in solitude.

You mentioned how you document in a natural way. This is in contrast to the overly retouched images that have come to characterize the social media/ digital age. What informs your approach?

You know we’re in the age of filters. Everything has a filter; everything is served in an algorithm. My work is the opposite of that. I grew up worshipping the African American photographer, Gordon Parks who is really instrumental in my style, a lot of his images are black and white images of people like Martin Luther King and Malcolm X and on the other side of his photography he’d be shooting Audrey Hepburn. I wanted to have that range as a photographer, and I wanted my imagery to look like it was intimate.

I don’t want you to look at my images and think it’s some sort of glossy universe that you’ll never have access to. I want you to look at the shots and feel like you climbed inside that image. If I could get anywhere near that I’d be very happy.

You’ve shot celebrities including Tom Cruise, Rihanna and Janet Jackson to name a few. What do you prefer, photojournalism or celebrity portraiture?

That’s an easy one, photojournalism every time, as lucky as I feel when I get to go shoot people like Janet Jackson. I had a well- documented meltdown when I met her. I just turned into my 13-year-old self. I actually ignored Rihanna. It was unbelievable but none of that compares to civil rights movements. The ability to do specific photo projects is something I’m working on at the moment that is linked to domestic abuse. That is for me, the purest form of photography, finding real people telling their story and having them allow you into their private sphere. That’s the greatest honour for me as a photographer.

You founded What We See on an interesting premise. What do you offer your audience?

I set that up as a response to what I call the weaponisation of mediocrity, which is the low rent, snackable, throwaway content that is frankly detrimental to our mental health. Let me put it this way. If you’re drowning in the noise of the internet, my medium What We See is a curated life raft of the very best of the internet brought to you so you don’t need to make excuses on why you would ever watch something like Love Island. There’s no excuse. Get on What We See, read some Langston Hughes poetry, listen to some Nina Simone. Do that and you’ll see how you’ll also learn more about who you are and who you want to be. That is why I set up the medium. I’m very lucky to work with everyone from BAFTA to CAA, Universal Music, Warner Music and a lot of artists. We recently developed beautiful conferences and had people like Emeli Sandé speak. We always try and have people talk about intimate and personal things about who they are. My pod cast is the same.

I’m asking people about their favourite songs and favourite scenes in films so we can paint this tapestry of everyone’s emotional engine and in some way help us understand who we are on this journey called life.

You have an encyclopedic knowledge of the arts from music, to poetry, to film, to art to photography. How did you grow from consumer to creator, parlaying great taste into a successful career?

At school I was always the kid that everyone would ask what film they should watch, what song they should listen to so without knowing it, l was curating then. I guess if I ever saw something that made me feel something, I wanted to share it with as many people as possible. What happened in later life is that my wife as only wives can do, watched me and said, “Its more than just a thing you do, this is a true gift”. When she started sending my playlists to her parents in Sweden and they were hooked, she said I need to share this with more people. That was one of the reasons I set up What We See. She also told me that my photography is unique so instead of obsessing over Annie Leibovitz, Gordon Parks, Sally Mann, etc. I should just try and create. She knew that I’d be good and that helped me believe in myself. I talk openly about my struggles with imposter syndrome and self-doubt. She was the oxygen that gave me the wings to not be afraid to try and the rest as they say, is history.

You’re happily married to Camilla and have two daughters, Isabella and Lyra. How are you and Camilla raising your girls?

It’s really important for our children to be children but we are watching them and making sure we provide for their passions. For example, Isabella our oldest, loves to paint and draw. We’re seeing if there’s any way we can help her. If she gets bored of it next year then there’ll be something else. It’s just always to nurture their passions and to never put those fires out and to allow them to dare to dream. That is something that as a father, l will always try and give my children.

And what would your late father, Chief Hope Harriman say about all this? We all know that trope of Nigerian parents and their conservative expectations for their children’s careers.

Ithink initially my father would have been like, “What is this camera?” Like your own father. They were good friends and they would have said, “Abeg, Tundun speak to Misan.” But I think he would have quickly seen that this more than just “play-play”. He would have said, “This is impressive” and would have aligned himself to helping me find my way. As I’ve gotten older, I’ve come to accept that our parents preferred traditional professional trajectories because they wanted us to have stability in life. Realistically, being black children as well, they would have thought that there are certain industries that would have been closed to us. Why would my father or my mother push me to be a photographer when they’ve never really seen any black photographer take it to heights that would be seen as incredibly successful? I definitely think my late father would have been reticent at first, but once he saw that I was able to do something with it, he’d be supportive.

Where in your mum’s house is your Vogue cover?

I got this box for her that with personal notes I’ve written.

Nigerian mothers have a special place in my heart because I know the depths of trials and tribulations they go through. For her to instill the ability to be the man that I am today is something that I really don’t take lightly. This Vogue cover is hers as much as mine, maybe even more hers than mine.

The collaborative nature of photography suits you perfectly with your great networking skills. You’re friends with everyone from Princess Beatrice who commissioned you for her official engagement photos to Meghan Markle to a few of my siblings and everyone in between from all races, ages and backgrounds. What is the importance of rapport and reputation in work and in life?

What I learned from my mother is never think you’re better than anyone else and always have your own voice. With a lot of people that I met that are high profile I think the reason they feel comfortable around me is that I’ve always been my true self. The slightly nerdy but always trendy man-child who is incessantly talking about some song or some film or photograph. I think people like to be around people like that because life in this Instagram age can be very much where people talk about how much they have. I’m always talking about how much we need to feel. There’s a difference there and I’m aware of that.

Mark Twain once said, “The two most important days in your life are the day you are born and the day you find out why.” You have these gifts that have found different expression throughout your life so has that day arrived?

I found my true calling just after I met Camilla. I realized through her telling me that I was put unto this earth to show other people how to feel, whether it’s a Pablo Neruda poem or a Joni Mitchell song. I guess society didn’t make me feel like that was any kind of superpower but now I’ve realized that its manifested itself in my medium What We See, in my photography, my friendships and my mentorship. I mentor a lot of people and help lift them in the way that I’ve been lifted throughout my life whether it was my mother or through Edward Enninful. I’ve always had people in my life that have let me know that I’m good enough and there’s nothing wrong with trying. I did a post today on Instagram saying that if you’re trying you actually cannot fail. I was recently in Wandsworth Prison mentoring some of the young men who have been incarcerated and I just talked about content. I didn’t talk about why they’re in prison. I just talked about films and music, things of cultural relevance. It was a really good way to reach them. You can’t defend yourself against great art. It seeps into your very soul.

Photography has been democratized by social media. Many more can take interesting pictures so how can budding photographers get noticed?

It’s a really exciting time for creatives

including photographers. People always talk about how bad the internet is but it’s a gift. I know many photographers that don’t have my network. Their work is so good that they’re reaching millions of people so I would say learn your craft. Put it out there on Instagram, Facebook and whatever social platform you like. You will see the universe will come to you but put in the work. Don’t expect that because you have a camera and you’ve taken a few pictures that you’re suddenly going to become the next Annie Leibovitz or the next Spike Lee as a filmmaker. You have to learn. A lot of photographers don’t understand the history of photography so I would say go on YouTube watch documentaries about the Photo League, the Jewish immigrants that came with nothing but their camera after they left Poland and other parts of Europe. Learn about Robert Capa and the history of Magnum Pictures. Learn about Gordon Parks. These documentaries are free. Understand the history of the still image. Throughout modern history, it’s been our time capsule, whether its pictures from the Vietnam War or Hitler’s Germany, the still image has been the thing that’s reminded us of who we are at our very worst and who we are at our very best. It’s a responsibility to know if you pick up a camera what you could achieved with it.

What’s your dream location for a shoot?

I would love to understand how to shoot on location in places that are difficult to shoot. I look at how they pulled off “Lord of The Rings” in New Zealand. And “Dances with Wolves” which was done in the frontier with no CGI. I think when you learn those skills as a filmmaker, you always have an authenticity. I would love to shoot in Italy, the Amalfi Coast then going more inland. I would do a beautiful romantic drama. Its Christmas in Lagos. Everyone is back home and the man sees a mysterious Nigerian woman who apparently lives in Italy. He doesn’t manage to get to know her. He meets her fleetingly and she’s off back to Italy. It’s about him on a whim going to traverse Italy to try and win her heart. There you go!

Photo credit: Camilla Harriman